On the 72 anniversary of the founding of the Indian Republic, what is clear is that one of the points of unity of this diverse nation is the allegiance to the Constitution. Yet allegiance may not be right word as when we say allegiance, we mean that we have a loyalty to a certain form of authority. As far as the Constitution is concerned, the feeling of the common people towards this document can perhaps more appropriately be described as a form of ‘constitutional love’.

The question of course is why do we have this attachment to the Constitution? Why is the Constitution important at all for us? Some scholars argue that too much is made of Constitutions. They are not that relevant after all, one can take the example of Great Britain which has subsisted for centuries without a Constitution. If Britain can do so, why do we insist on not only having a Constitution but giving it the reverence due to royalty?

Great Britain though it does not have a constitution, it does have a constitutional tradition and a deeply rooted sense of constitutional morality. This Constitutionalism which is part of the British tradition stems from a history of struggle. Perhaps the most important landmark in the British constitutional tradition was the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215 which guaranteed that, ‘no free man’ could be imprisoned or lose his possessions except by ‘the law of the land’. In simple terms what this clause of the Magna Carta lays down is the principle of rule of law which is that punishment for a crime must be authorized by law and that no person can be detained without the authority of law.

This principle laid down in 1215 AD, still animates not only English jurisprudence but has become a part of the mental furniture of the British people. In short a constitutional principle has become a part of ways of thinking of common people to such an extent that even during World War II at the height of the Nazi threat, preventive detention was an exception (to be justified on a case to case basis with adequate documentation justifying the detention) and not the rule.

When it comes to India, though we have a Constitution, constitutional morality has not yet become a part of the way the state acts. No example better illustrates the fact that the state has not imbibed a constitutional morality than the continued detention of what is now referred to as the Bhima Koregoan sixteen.

A completely false case has been filed in the context of the violence in Maharashtra during the Bhima Koregaon celebrations against sixteen human rights activists from around the country, whom the State found troublesome. What is shocking is that many of them such as Sudha Bharadwaj, Anand Teltumbde and 83 year old Father Stan Swamy had no connection to the Bhima Koregaon incident. They were still arrested under the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act and continue to languish in jail.

Also Read: An Uproar Against the Arrest and Inquiry of Veteran Scholar Hampana

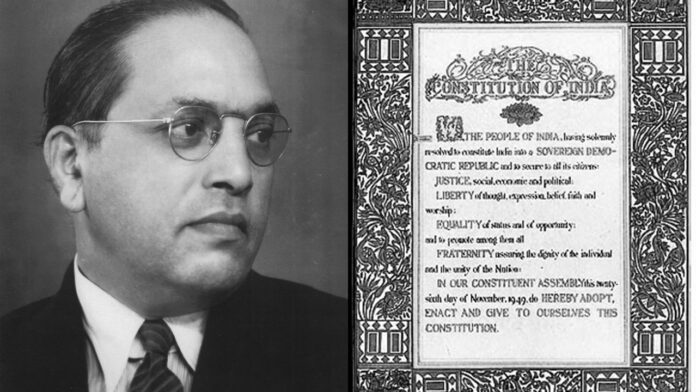

Part of the reason that these kinds of violations continue to happen in India is not only because the state does not act on the basis of constitutional morality but also that constitutional morality lacks deep roots in the people. Nobody captured this better than Dr. Ambedkar who said:

Constitutional morality is not a natural sentiment. It has to be cultivated. We must realise that our people have yet to learn it. Democracy in India is only a top dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic.

Just as the idea of the ‘free born Englishman’ is now part of the British constitutional tradition, the idea of the ‘free born Indian’ who cant be subjected to imprisonment at the whim and fancy of the state must become a part of a wider societal thinking.

This has been the effort of human rights movements in India which have not only sought to ensure that the state does not trespass constitutional limits but also that the value of ‘freedom from arbitrary arrest’ is more deeply seeded in popular consciousness.

One way of seeding these ideas more deeply is to go back to ideals animating the independence struggle and the role played by Gandhi as an exemplary fighter for political freedom. Gandhiji taught us that freedom had no meaning if the state continued to lock up its opponents. He fought for the idea that the state had no right to lock up its opponents without trial and without legal representation. This was the impetus behind the nationwide civil disobedience movement which was waged to repeal the draconian Rowlatt Act which bears parallels to today’s Unlawful Activities Prevention Act.

The Rowlatt Act departed from the principles of criminal law by removing all the safeguards to which the accused were entitled, including the right to be safeguarded from pre-trial detention; legal representation; and a public trial in open court.

Not surprisingly, the Rowlatt Act outraged Indian public opinion and led to a series of protests and demonstrations across India. A report authored by Gandhi on the Acts concluded: “[I]t is this Act, which raised a storm of opposition unknown before in India. […] In our opinion, no self respecting person can tolerate what is an outrage upon society.”

If we are to think of a constitutional tradition as an outcome of struggle again we can go back to Gandhi’s famous words when he is charged with sedition. Sedition is an offence of ‘exciting disaffection against the state’. Regarding this charge of sedition, from the prisoner’s dock Gandhi reads this statement:

Section 124-A under which I am happily charged is perhaps the prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen. Affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by law. If one has no affection for a person or system, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote or incite violence…I hold it to be a virtue to be disaffected towards a Government which in its totality had done more harm to India than any previous system.

In the contemporary context those arrested on the pretext of the Bhima Koregoan case are doing nothing other than what Gandhi did, namely, ‘giving the fullest expression to their disaffection’, by their speech and writings. The arrested, be it Sudha Bharadwaj, Anand Teltumbde or Stan Swamy are articulating the concerns of the Dalits and Tribals and in the process critiquing the policies of the government. This is an opinion which the government may not like, but if it is to proceed on the basis of constitutional morality, it has no right to censor through prolonged incarceration.

It is an imperative that the government acts in accordance with constitutional morality which encompasses the values of values of liberty, equality and fraternity and justice. If it does not, it is the task of ordinary citizens to compel the government to respect the rights which are recognized by the Constitution of India.

Arvind Narain is a Founding Member of Alternative Law Forum in Bengaluru, a collective of lawyers who work on a critical practise of law.

[…] Also read: Constitutionalism at 72 […]