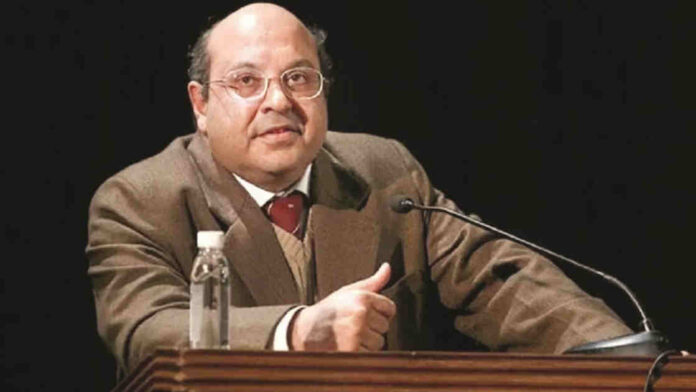

Justice Rohinton Nariman retired on August 12, 2021, after seven years on the Supreme Court. His retirement saw a series of articles by Senior Advocates including Indira Jaisingh, Anand Grover, Sanjay Hegde extolling his record on the Court.

In Chief Justice Ramana’s words, ‘With brother Nariman’s retirement, I feel like I am losing one of the lions that guarded the judicial institution’.

The unstinted praise for Justice Nariman stood in sharp contrast to the severe criticism that Justice Bobde faced when he retired. The contrast speaks to two different judicial approaches which characterize the Supreme Court.

There are judges who are willing to stand up for the values of the Constitution and judges who are ‘more executive minded than the executive’, forgetting their oath to defend the Constitution. Judges who secure their place in history are those who are not afraid to take on the executive in defense of the Constitution.

The judge who history knows is Justice Khanna who delivered the dissent in the Supreme Court judgment which legitimized the emergency and not Chief Justice Beg who delivered the infamous emergency judgment.

Justice Nariman has made clear his admiration for Justice Khanna’s clear-sighted defence of fundamental rights. In a number of important judgments, he has deepened the judicial understanding of the scope of fundamental rights.

Among the notable judgments he has authored are Shreya Singhal (striking down Section 66A of the Information Technology Act), Puttaswamy (holding that the right to privacy is a protected fundamental right in the Indian Constitution), Shayara Bano (striking down triple talaq), Navtej Singh Johar (reading down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code), Indian Young Lawyers Association (permitting entry to women in the Sabarimala temple in Kerala), Paramvir Singh Saini (directing the installation of CCTV cameras in police stations).

Using Law as a Counter-Majoritarian Instrument

What defines Justice Nariman’s way of thinking, is that for him, the individual right to dignity, privacy, and expression had to be protected regardless of what the majority thought, because that is what the Constitution mandates. What crystallized this way of thinking about the law as a counter-majoritarian instrument were three judgments which he (along with justices Chadrachud, Mishra, Khanwilkar, and Misra) delivered in September of 2018.

In Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India in 2018 the court held that Section 377 of the IPC which criminalised same-sex conduct, violated the right to dignity and liberty of LGBT persons. In Joseph Shine v/s Union of India in 2018, the court struck down Section 497 of the IPC which criminalised the act of adultery by a man.

Also read: Same Sex Marriage is Not a Fundamental Right: Central Government to the Delhi High Court

The court held that the law on adultery embodied a ‘patriarchal’ understanding of sexuality which was antithetical to a constitutional morality based on a commitment to the ‘free, equal, and dignified existence of all members of society.

Justice Nariman and the Sabrimala Judgement

In Indian Young Lawyers Association v State of Kerala in 2018, the Supreme Court struck down the regulations prohibiting women from the age of ten to fifty from worshipping at Sabarimala arguing that ‘the menstrual status of a woman is deeply personal and an intrinsic part of her privacy’ and cannot be the basis on which ‘exclusion can be practised’ and ‘denial perpetrated’.

The court explicitly held that in the ‘constitutional order of priorities’, the ‘individual right to freedom of religion’ was subject to the ‘overriding constitutional postulates of equality, liberty and personal freedoms’.

However, this brief efflorescence of what the court called ‘constitutional morality’ and ‘transformative constitutionalism’ was quickly reversed. What signposted the retreat of the court from espousing constitutional morality was the unprecedented decision by the bench constituted to review the Sabarimala judgement.

The review jurisdiction is legally and constitutionally a narrow one where the court examines if there is an ‘error apparent on the face of the record’, and if there is no such error, the review petition is dismissed.

The fact that the Court chose to not dismiss the review in Sabrimala, inspite of petitioners failing to demonstrate that there was an ‘error apparent on the face of the record’, speaks to the political exigencies the court was responding to.

The period following the Sabarimala verdict witnessed violent protests against the judgment. The charge against the judgment was led by the ruling BJP and the RSS, with the then BJP president Amit Shah openly calling for the disobedience of the Supreme Court verdict.

He went on to ‘advice’ the court to ‘desist from pronouncing verdicts which cannot be implemented.’ It was unprecedented to have the president of the ruling party, publicly advocating that the judgment of the Supreme Court must not be followed.

In their response to this veiled threat to the court to not privilege constitutional morality over majoritarian religious sentiment, the court, instead of standing its ground, buckled. Justices Gogoi, A. M. Khanwilkar, and Indu Malhotra signed on to the majority opinion, going beyond the ambit of the review and allowing for the matter to be relitigated again.

The minority opinion by Justices Chandrachud and Nariman gave a sense of the pressures which may have led to reopening the Sabarimala verdict. As both judges noted, ‘extreme arguments were made by some learned counsel stating that belief and faith are not judicially reviewable by courts’. The judges noted that ‘such arguments need to be rejected out of hand’ as they flew in ‘the face of Article 25’.

The judges were merely reiterating what Article 25 stated which was that though a person has the constitutional right to profess, practice, and propagate the religion of one’s choice, such a right had to be subject to other fundamental rights like the right to equality and dignity.

Also read: Rise of Love Jihad Laws and Legislative tools of Surveillance: New Age Manusmriti for Women

The minority judgment’s meaning was quite clear: the political executive was expressing an opinion clearly at odds with the Constitution and it deserved to be rejected.

The minority held, ‘It is necessary for us to restate these constitutional fundamentals in the light of the sad spectacle of unarmed women between the ages of 10 and 50 being thwarted in the exercise of their fundamental right of worship at the Sabarimala temple.

Let it be said that whoever does not act in aid of our judgment, does so at his peril—so far as Ministers, both Central and State, and MPs and MLAs are concerned, they would violate their constitutional oath to uphold, preserve, and defend the Constitution of India.’

Justice Nariman’s dissent in the Sabrimala review petition shows him as someone who did not kowtow to the executive in the discharge of his judicial responsibilities. He felt very strongly that the constitutional values of respect for dignity and privacy of the individual could not be sacrificed at the altar of majoritarian sentiment.

What best captured his thinking about the role of a judge in safeguarding fundamental rights in a time of majoritarianism was his opinion in Navtej Singh Johar. As he put it:

The very purpose of the fundamental rights chapter in the Constitution of India is to withdraw the subject of liberty and dignity of the individual and place such subject beyond the reach of majoritarian governments so that constitutional morality can be applied by this Court to give effect to the rights, among others, of ‘discrete and insular’ minorities. One such minority has knocked on the doors of this Court as this Court is the custodian of the fundamental rights of citizens.

These fundamental rights do not depend upon the outcome of elections. And, it is not left to majoritarian governments to prescribe what shall be orthodox in matters concerning social morality.

The fundamental rights chapter is like the north star in the universe of constitutionalism in India. Constitutional morality always trumps any imposition of a particular view of social morality by shifting and different majoritarian regimes.

We need more judges like Justice Nariman who see the Fundamental Rights Chapter as the ‘north star’ and are willing to protect the rights of unpopular minorities to dignity and selfhood, regardless of what the majority may think because that is what the Constitution mandates.

Also read: Madras HC Calls CBI ‘caged parrot’, Asks Union Govt to Make it Autonomous