The article is part of our series on migration.

“You can’t fight against the word ‘illegal’,” points out Chinmay Tumbe, who teaches Economics at IIM-Ahmedabad, “if you use the word ‘illegal’, the NRC becomes appealing.”

The current argument for implementing the NRC is that illegal immigrants take away local jobs because they provide cheap labour. Immigrants also supposedly pose a security threat to the country. The large volume of immigrants in India is seen as a drain on national resources. But the numbers being touted by politicians and doing the rounds on social media may be completely baseless.

“Sometime around the ‘90s and 2000s, this number started floating around: twenty million,” Tumbe says. “There was a rumour that this number came from an army general who made an estimate based on border crossings. But there was absolutely no basis for nor any proper methodology involved in arriving at this number.”

Also Read: National Register of Citizens: How the BJP is turning regional conflicts into national campaigns of hate

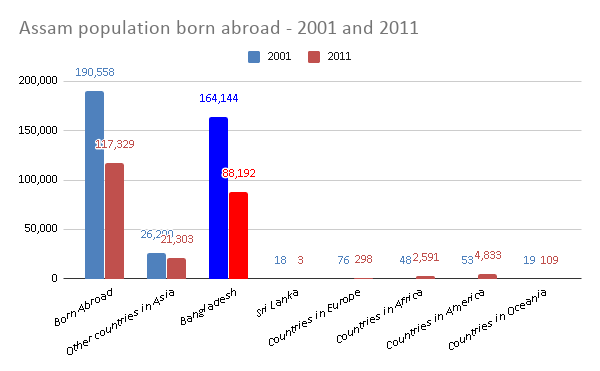

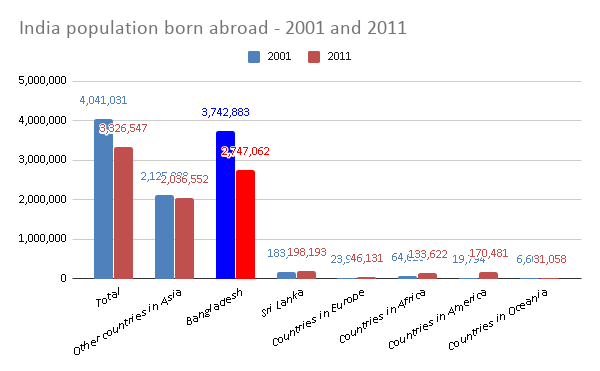

Recently released NRC data on migration shows that in fact, the number of undocumented migrants in Assam is approximately 1.9 million, or 19 lakhs. To put this in perspective, the population of India is 1.3 billion, or 137 crores, making the migrants in Assam 0.001% of the total population. Considering that the North-East, specifically Assam, has the largest volume of immigrants in the country, Tumbe estimates that there can’t be more than 2.5 million undocumented immigrants in total, which means that the percentage still stays at 0.001.

As to the question of why there are this many immigrants, Tumbe says: “You don’t see any migration in the world without demand. These people provide labour, but with particular techniques. And these are the same people who have been doing this for generations now, so they have certain skills for which there is a demand – especially in agricultural labour.”

This puts the alarmist rhetoric surrounding illegal immigration in a new light. After all, it makes sense, especially considering the large Indian and Pakistani diaspora in places like the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Most of us know at least two or three people who have emigrated from India to the Gulf, and who have perhaps overstayed their visas and settled down – but we would never consider them a security threat in any way.

“These people are undocumented migrants – and they’re not undocumented terrorists, they’re undocumented workers,” Tumbe points out. “Are they dangerous to India? No. They’re coming as workers! And why are they undocumented? Either because they’re escaping adverse conditions so it’s out of desperation, or because they came legally, on a permit, and they didn’t want to go back, so they overstayed.”

Neither of these two types of migrants are dangerous, at least at face value, to either the economy or to national security. There is no evidence whatsoever for undocumented migrants stealing jobs or engaging in terrorist activities. So then what is at the root of all the alarm?

“A lot of it is political rhetoric,” Tumbe suggests, “There are people with genuine concerns – and it is true that immigration in certain districts is very high in terms of the percentage of the population – but to take the argument from a few districts of India to all the 700-odd districts of India makes no sense.”

The districts in which immigration is the highest all lie in the North-East. The natural, mountainous border on India’s Western front means that it is nearly impossible to cross over; the case is different on its Eastern front. During India’s war with Pakistan in 1971, there was a large influx of refugees from East Pakistan, which then became Bangladesh. However, very few stayed on, and the ones that did acquired Indian citizenship. Between the 70s and 80s, however, there was considerable economic pressure to come to India. “This migration for the first time gets the colours of ‘illegal immigrants’”, Tumbe explains. Census data shows that in fact, between 2001-2011, the number of incoming immigrants from Bangladesh is reducing. In the last ten years, the Bangladeshi economy has improved, and research on Bangladeshi emigration shows that its citizens are going to the Gulf and Europe rather than coming to India.

But the NRC is not really about numbers and hard facts. Rather, “[the] ‘illegals’ bogey is not so much about immigrants in general, but more about Muslim illegal immigrants, as in Western Europe”, points out Tumbe. According to the government, “Tibetan Buddhists are fine, Sri Lankan Hindus are fine, but Rohingya Muslims are not, Bangladeshi Muslims are not. So we know who’s going to be threatened by this. The NRC provides additional scope for harassment [of Muslims] – and at the end of the day, that is precisely why it is being done,” Tumbe states, “it’s a classic diversionary measure.”

Also read: Democracy under Detention: Report details horrors of NRC in Assam

Moreover, the NRC doesn’t make sense from a cost-benefit perspective, a quick analysis makes that obvious. The government has already spent about 1000 Crores on the NRC in Assam – a 1000 Crores that could’ve gone into Swachh Bharat, Child Development Services, MNREGA, or any other nationally beneficial scheme. It’s true that 19 Lakh people have been identified – but what is the next step? The government can’t deport them, because there is no deportation agreement with anyone. This shows that the money and time spent on the NRC is for something other than tangible, material benefits.

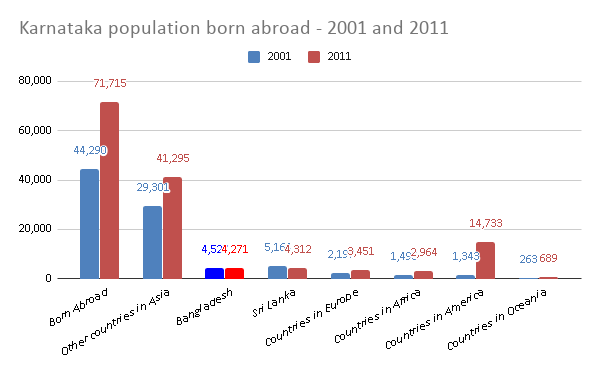

As for implementing it in Karnataka – which BJP MP Tejasvi Surya, among others, has called for – the prospect makes no sense. Tumbe estimates that the number of undocumented migrants in the state might be a few thousands. To implement it here would mean putting nearly everyone in hardship in order to single out the 0.001% – in Karnataka’s case, even less. “From a priority perspective, it just doesn’t make sense,” Tumbe notes.

The government and the citizens clamouring for the national implementation of the NRC need to keep these things in mind: the lack of evidence that undocumented migrants are harmful to the economy, the lack of evidence that they are a security threat, and the communal flavour of the rhetoric surrounding the NRC – not to mention the fact that actually implementing it amounts to little more than a canny political chess move. Do we want India to stay colourful, multi-ethnic, and multilingual? Or do we want to be a country that weeds out the helpless and the hopeless, targeting those who have next to nothing?

Chinmay Tumbe is a faculty member at IIM-Ahmedabad and author of India Moving: A History of Migration.

Many thanks to Divij Sinha of the Indian Institute for Human Settlements for his help with interpreting Census of India data.

[…] Read More: “All-India NRC Makes Absolutely No Sense”, Says IIM Professor […]