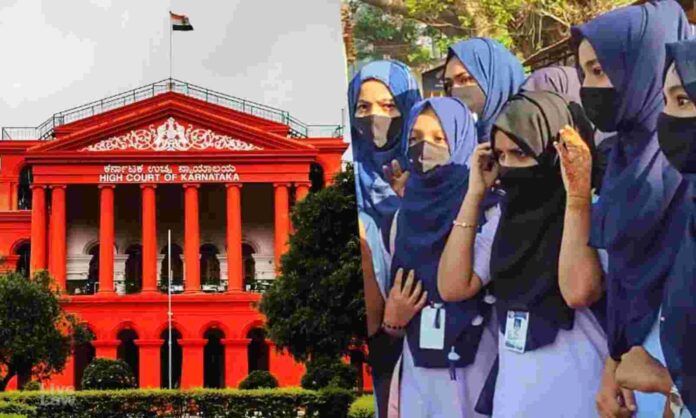

On 13 October 2022, the 2-member bench of the Supreme Court delivered a split verdict regarding the Karnataka Government Order allowing Colleges to ban the wearing of hijab by students in classrooms. The case was heard by Justice Hemant Gupta and Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia. Justice Gupta dismissed the petition to appeal the Karnataka High Court, “though on different grounds than what prevailed before the High Court.” Justice Dhulia allowed the appeals. As a result of this split verdict, the case will be referred for consideration by a larger bench.

The judgment: Rights of the State vs Rights of the Students

On one side, was Justice Gupta, who dismissed the appeal. In Gupta’s judgment, he interpreted secularism as the removal of religion from the state. As he put it, “religion cannot be intertwined with any of the secular activities of the State. Any encroachment of religion the in secular activities is not permissible.” His judgment then proceeded to address various questions raised in the trial. He declared that “it is open to the students to carry their faith in a school which permits them to wear Hijab or any other mark, may be tilak, which can be identified to a person holding a particular religious belief but the State is within its jurisdiction to direct that the apparent symbols of religious beliefs cannot be carried to school maintained by the State from the State funds.” While on the face of it, it may seem fair, since the case did not involve students wearing tilak, or markers of other religions, the example would only be relevant when students of other religions are forced to remove religious markers by way of a ban, so this call for equality will not work against markers of the majority religion unless those markers challenge a status quo.

His judgment showed that a state-run college need not be as pluralistic and tolerant as the public space, and the state is within its right to issue an order against the wearing of the hijab to promote uniformity among the students in a Government College. “The right to education under Article 21 continues to be available but it is the choice of the student to avail such right or not. The student is not expected to put a condition, that unless she is permitted to come to a secular school wearing a headscarf, she would not attend the school. The decision is of the student and not of school when the student opts not to adhere to the uniform rules.”

On the other side, Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia stated that the ban was unreasonable and even contrary to a just vision of society. He said that “It does not appeal to my logic or reason as to how a girl child who is wearing a hijab in a classroom is a public order problem or even a law-and order problem. To the contrary reasonable accomodation in this case would be a sign of a mature society which has learnt to live and adjust with its differences.”

In the Indian context, diversity of expression is vital to the democracy of India as, as Justice Dhulia pointed out, “It is the Fundamental Duty of every citizen, under Part IV A of the Constitution of India to ‘value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture.’”

On a more personal level, adoption or non-adoption of religious markers is a personal choice. “Under our Constitutional scheme, wearing a hijab should be simply a matter of Choice. It may or may not be a matter of essential religious practice, but it still is, a matter of conscience, belief, and expression.”

Looking at the ban

The ban on hijab in public spaces has exposed the undemocratic nature of the Indian educational space. Repeated at both the High Court and the recent Supreme Court hearing, was that the education administration could, without proper notification, without proper engagement with relevant stakeholders, without options for reasonable accommodation, without issuing stay periods until the matter could be resolved, and without investigating the impact of their direction, could issue and implement the ban. In effect, the education system has taught the people that it is not bound to the needs of the students.

Looking beyond the ban

Even beyond the ban, the application of the ban was contrary to basic democratic principles. Women were suddenly placed into situations where they had to make choices between a form of clothing they were accustomed to, and their education. Many students have taken Transfer certificates, and many have dropped out completely. Even among those who have not dropped out or transferred, many women have faced harassment and stress in their pursuit of education. Student transfers effectively would divide the state between educational institutions that ban headscarves and those that do not. Student dropouts, especially women from low-income households, will affect families, especially those from low-income groups, for generations to come. Beyond the verdict of the case, the ban has done damage to the social fabric, which may last for years to come.

What of the rights and time lost?

Already, the ban has wreaked communal havoc across the state of Karnataka. Even in districts where such communal tensions were unheard of, the hijab ban has catalyzed right-wing forces. This damage will not be addressed in the later hearing, and the split verdict has prolonged the struggle.

Many women have had to struggle with their rights being taken away. The right of the state to restrict rights has been pitted against the rights of the Indian people since the time of independence. Even in this case, the right of the state to impose restrictions is pitted against the right of a woman to her conscious. In Gupta’s judgment, Muslim women need to make themselves part of a uniform society, which seems to only exist in certain settings and not society as a whole. Their democratic voices are irrelevant. The case raises important questions about the nature of education as provided by the state: Are these spaces of education supposed to represent the true society? Are they supposed to represent an aspiration of society? Whose aspirations should they represent?

The author is a mathematician and political observer based in Bangalore.