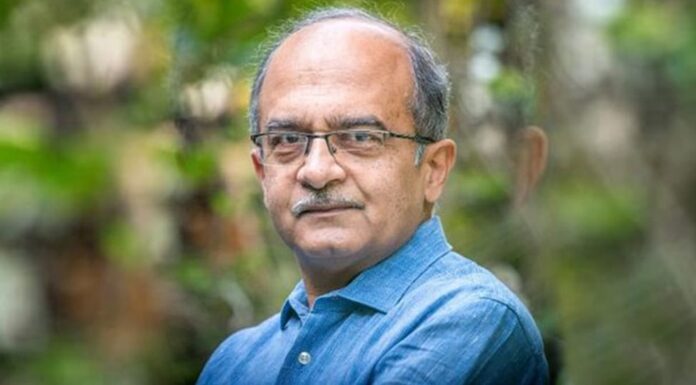

The Supreme Court has found Prashant Bhushan guilty for contempt for two tweets both of which the Court found ‘undermines the dignity and authority of the institution of the Supreme Court of India and the CJI and directly affronts the majesty of law’. The tweets were also seen by the Court as undermining the ‘the trust and the confidence of the people’ in the ability of the judiciary to ‘deliver fearless and impartial justice’.

By this judgement, the Supreme Court narrowed the protection given to freedom of speech and expression and ignored its own jurisprudence where the power of contempt was to be invoked rarely. Its worth recalling Justice Krishna Iyer’s understanding in Re: S. Mulgaokar, where he wisely observed that, ‘court is willing to ignore, by a majestic liberalism, trivial and venial offences – the dogs may bark, the caravan will pass.’

However in this case the Supreme Court seems to have ignored Justice Krishna Iyer’s dictum and preferred to see the two tweets as having the effect of shaking public confidence in the administration of justice. This is a puzzling conclusion as Prashant Bhushan’s reply affidavit elaborately documents, the kind of criticism levied by Prashant Bhushan has been levied not just by legal academics and media commentators but also by former judges of the Supreme Court.

This thin skinned approach of the Court sits uneasily with other democracies where the power of contempt has been read narrowly by the Courts.

In the United Kingdom, Lord Denning observed as follows: “Let me say at once that we will never use this jurisdiction as a means to uphold our own dignity. That must rest on surer foundations. Nor will we use it to suppress those who speak against us. We do not fear criticism, nor do we resent it. For there is something far more important at stake. It is no less than freedom of speech itself. It is the right of every man, in parliament or out of it, in the press or over the broadcast, to make fair comment, even outspoken comment, on matters of public interest’

In the United States, the offence of “scandalizing the court” has been limited in application for several decades. The Supreme Court has made it clear, in a series of cases, that the publication must create a “clear and present danger” to the administration of justice, if contempt is at all to be invoked.

In Canada, in the case R V. Kyoto, when a lawyer criticized the decision calling it a ‘mockery of justice and stating that ‘it stinks to high hell’, the Court noted that, ‘Some criticism may be well founded, some suggestions for change worth adopting. But the courts are not fragile flowers that will wither in the hot heat of controversy..’

The Law Commission of Australia disagreed with the core reason why contempt was on the statute books noting, ‘The rationale of the offence, namely, the undermining of public confidence in the administration of justice seems highly speculative and some might say that it is too vague a principle to justify imposing restrictions upon freedom of speech.’

In contrast, the law on contempt has been kept alive in the ex-colonies. In fact nineteenth century case of McLeod v. St. Aubyn, the Privy Council argued that ‘Committals for contempt of court by scandalizing the court itself have become obsolete in this country’ … ‘But it must be considered that in small colonies, consisting principally of coloured populations, the enforcement in proper cases of committal for contempt of court for attacks on the court may be absolutely necessary to preserve in such a community the dignity of and respect for the court’.

It is this colonial legacy of insulating the Courts from criticism which is being continued when the contempt jurisdiction is invoked. Even though the power of contempt is constitutionally recognized, its important that its use should be limited keeping in mind the fact that the Constitution recognizes that Indians today have the freedom of speech and expression.

Again it is Prashant Bhushan’s reply affidavit, (which the Court in a failure of due process does not even advert to in its judgment) which painstakingly substantiates the two tweets, letting us know how the Court has failed to perform its constitutional duty. The reason why citizens need to stand up today, is because if we go back to the emergency era, as Prashant Bhushan put it, ‘It is a matter of historical record that it was not the institutions and the erudite and learned people manning them that stood up for the Constitution and its democratic values, but ordinary citizens who fought for their democratic rights.’