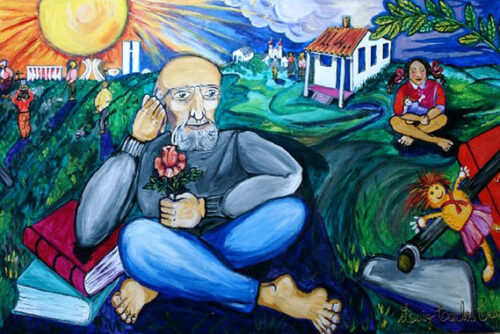

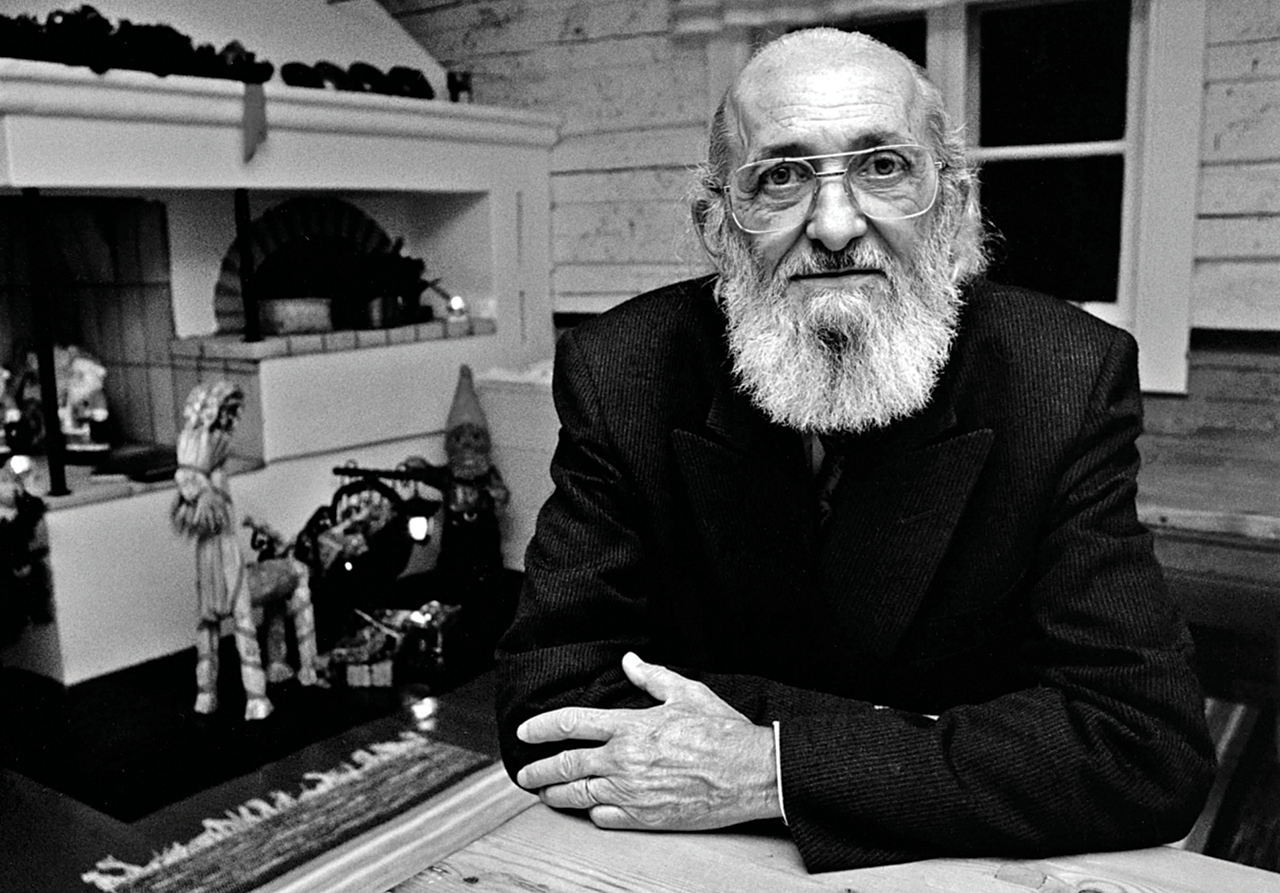

Born to a middle-class family in Recife, in the state of Pernambuco in northeast Brazil, South American philosopher Paulo Reglus Neves Freire’s (1921-1997) life experience shaped his vision of education. In his younger days he faced hunger, poverty and personal hardship because of the economic depression in his country. The turning point in his life came when Aluízio Pessoa de Araújo, the principal of a secondary school gave him an opportunity to study in his school at a reduced tuition fee. This happened to be his only life chance at formal education. To reciprocate this generosity he decided to teach in the same school in 1942. In 1947 he was invited to join a government agency called the Serviço Social da Indústria (SESI) where he began to work with the illiterate workers and peasants in Brazil. His teaching-learning experiences during these years in SESI lead him to develop adult literacy methods that are practiced the world over even today. He wrote and published extensively about his actions and reflections. One of Freire’s best-selling works, first published in 1971, is Pedagogy of Oppressed that has sold more than a million copies worldwide. In 2018 Bloomsbury published its 50th anniversary edition with a foreword by Noam Chomsky. It is widely regarded not as an ordinary book but ‘a transformative text’. There is renewed salience in re-reading Freire’s illuminating book at the current juncture. His longtime political ally and Brazil’s first working-class president Lula da Silva has re-returned to office after winning the October 2022 election. His radical ideas merit a re-visit on his death anniversary now as he continues to remain an inspiration to all educators who believe in social justice (Madan, 2022). Pedagogy of the Oppressed remains relevant because it dreams of an egalitarian, inclusive and just social order through education in socially-divided Brazil notwithstanding poverty, unemployment and inequality. This kind of socio-economic inequality is exacerbating in many countries including India. Also, post-colonial societies like ours have inherited colonial educational apparatuses that are disconnected from the life of their majority people.

It is noteworthy in this context that commentaries have pointed out that sometimes international financial agencies have in a ‘pseudo-Freirean perspective’ worked in the direction of reinforcing prevailing structures of oppression in unequal societies rather than liberating Third World’s peasants from the domination of private capital (Kidd and Kumar, 1981). A reading of Freire’s original works is valuable for an authentic re-conceptualise of education for transforming a society towards humanisation, social justice and empowerment of the poor. Also, the language of the book has been regarded as inaccessible to a non-specialist reader. This article attempts to understand three core terms of Freirean vocabulary: banking education, problem-posing education and dialogue, as presented in this illustrious book.

Banking Concept of Education

Freire came to realize that the sole purpose of education of his times was to transmit information to students who were presumed to be passive beings, or, empty vessels. Teaching was seen as a task of deposition of information in the name of knowledge. The knowledgeable teacher supposedly deposits it in the students mind, much like a banking process. In such a type of education it is the efficiency of teachers’ deposition and students’ passivity that defines their respective proficiency as,

The capacity of banking education to minimize or annul the student’s creative power and to stimulate their credulity serves the interest of the oppressors, who care neither to have the world revealed nor to see it transformed (1993:47).

Such an education is apolitical as well as devoid of possibilities for the rural and urban poor to raise their own problems ‘of agriculture, health, livelihood and ownership of factors of production’ (Raina and Mansi, 2022). Freire believed that it is a tool used by the oppressors to maintain their authority on the oppressed by making them mere meek receptors of existing ideas legitimizing the status quo of inequality in society.

Problem-posing education

Freire, a man of action, offered an antidote: problem posing education, as liberation from the dehumanizing effects of banking education. Problem posing education, instead of centering on textbook knowledge, assumes reality as a dynamic process of transformation that addresses the immediate problems faced by people in their own environment. He writes,

The problem-posing method does not dichotomize the activity of the teacher-student: he is not ‘cognitive’ at one point and ‘narrative’ at another. He is always ‘cognitive’, whether preparing a project or engaging in dialogue with the students. He does not regard cognizable objects as his private property but as objects of reflection by himself and the students (1993:54).

In this pedagogical approach, problems from the outside world are presented to the students as the educational content. Both students and teachers find out ways to solve these problems. Freire did not see education as merely mastering of academic standards or skills that prepared ‘professionals’ but as a humanizing process that developed learners who understood their social problems and discovered themselves as creative agents. Such an education transforms the students from the objects to the subjects of the process of education by overcoming both authoritarianism and their false perception of reality.

Dialogue

The foundation of problem-posing education is Freirean dialogue. A problem posing education can only be dialogical as it needs to be based on meaningful dialogue about real life and its problems; between teachers and students. Unlike banking education it isn’t just intellectual or text bookish in mode but,

Education which is able to resolve the contradiction between teacher and student takes place in a situation in which both address their act of cognition to the object by which they are mediated. Thus, the dialogical character of education as a practice of freedom does not begin when the teacher-student meets the students-teachers in a pedagogical situation, but rather when the former first asks himself what his dialogue with the latter will be about (1993:65).

Freire has gone as far as to call dialogue an existential necessity. For him human existence can never be silent because to live humanly means to speak with each other and transform the world together. It is necessary to break the culture of silence implicit in the banking model of education leading to educational practice that involves a real-world action beyond the abstract apolitical world of textual knowledge.

Educational practice in post-colonial societies

Freirean educators are confronted with the complex relationship between politics, history and social change. Most post-colonial societies like India have institutionalised a banking model of school education characterized by a tightly framed, predefined school curriculum which is mostly indifferent to human realities. Teachers are expected to transact the copious chapters of several textbooks of the many school subjects. These chapters constitute the credit that has to be put in the bank which is the student. The government’s education department, which serves as the certifying and standard-setting body, expects that the students have a basic understanding of the material covered in these chapters. The tends to an anti- dialogical tonality as the teacher teaches and the students are taught. The teacher talks and the students listen; the teacher presents disciplinary knowledge and the students follow it. The teacher remains the subject of the learning process, while the students become its objects. Freire distrusted formal school curriculum, as according to him education should be based on generative themes from the student’s real life. The exploration of these themes should be dialogical which can provide an opportunity to stimulate learner’s awareness regarding the themes. Problem-posing education aims to liberate humans, of which the first step is to break the authoritarianism between teachers and students, which is not possible in a transmission model of banking education. The educational systems in most societies (global south in particular) follow a vertical relationship between teachers and students where communication (not dialogue) is between the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teachers obviating a pedagogy of hope. Yet reading Freire continues to keep alive the dream of education for social justice among educators the world over.

References

- Freire, P. (1971/ 1993). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. England: Penguin.

- Kidd, R. and Kumar, K. (1981). ‘Co-opting Freire: A critical analysis of pseudo-Freirean adult education’, Economic and Political Weekly, 16(1-2), 27-35.

- Madan, A. (2022). Book Review Walter Omar Kohan, Paulo Freire: A Philosophical Biography (Jason Wozniak & Samuel D. Rocha, Trans.), London: Bloomsbury, 2021. 296 pages INR 1742 (E-book). Contemporary Education Dialogue. 19(1), New Delhi: Sage.

- Raina, J. and Mansi. ‘Education in post-colonial societies and Paulo Frere’s Insights’, The Armchair Journal, 21 August, 2022.

(Jyoti Raina teaches at the Department of Elementary Education at Gargi College, New Delhi. Mansi is her student at a four year undergraduate pre-service teacher education program at the same department.

The article was first published in Countercurrents.org.