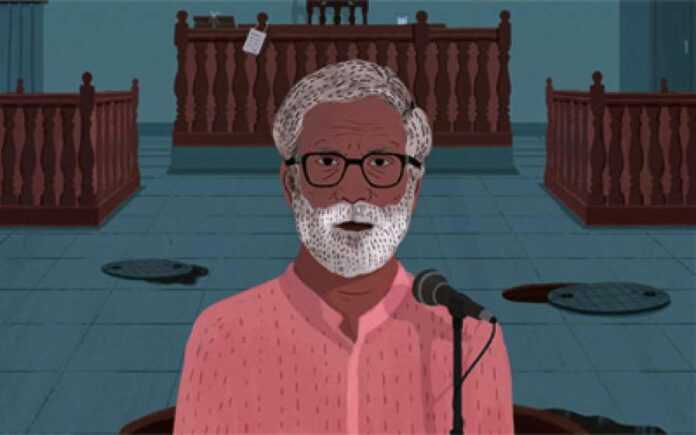

The Marathi movie Court (directed by Chaitanya Tamahane) centers around the realistically-absurd trial of a Dalit folk singer, who is charged with Abetment of Suicide. He is accused of abetting the suicide of a Dalit sewage cleaner, Vasudev Pawar, through the messages conveyed in his songs. The film critically analyzes the Indian Judiciary, exposing its biased, archaic and tedious aspects. The main aspect highlighted in the film is the systematized, state-sponsored caste oppression that exists in and around our legal system.

The Constitution of India explicitly prohibits discrimination on the basis of caste, which formally banned casteism in India. Various other legislative measures, including the Untouchability Offences Act and the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes Act, have attempted to curb the practice of untouchability and integrate marginalized groups into society. However, although formally the caste system may be unlawful in India, the aftermath of India’s ridding of untouchability has merely been an extension of the period when untouchability was legal. Although the relationships are altered, subordination subsists long after it has formally ended.

Read More: Shree 420: Why this Masterpiece from Raj Kapoor needs a revisit

It is ingrained in the minds of this very society that the Dalits are inferior. Thus, they can never truly escape the system that brands them as untouchables. Practically, the inescapable nature of the caste system can be observed by the kind of work taken up by these marginalized sections. Common professions include undignified work such as sewage cleaning, manual scavenging, amongst others. This aspect is depicted in the movie through the character of the deceased (Vasudev Pawar) in the case. When his wife is called to be cross-examined in Court, the viewers get a vivid idea of the working conditions Pawar is made to work in.

Another evidence of this is the conversation the defence attorney, Vinay, has with Vasudev’s wife. She asks him if he knows of any work and informs him that she is “willing to work anywhere”. One can presume that despite her willingness, she has struggled to find work for herself. This statement, although delivered with complete nonchalance (in keeping with the rest of the movie), leaves a lasting impression on the mind of the viewer as it is indicative of the extent of her marginalization in society.

It is interesting that in the multiple courtroom scenes, there is no use of the term ‘Dalit’ or any such related term. In fact, there is no mention of the lower-caste status of the accused. Although all of his “crimes” have a strong relation to an anti-oppression struggle, it is an angle not explored in the court. During the trial, Kamble is branded a nuisance and is painted as a threat against the State, but is never called what he really is; a Dalit. This diverts from the actual context in which Kamble sings his songs. It is true that the term Dalit, rather than being an oppressive term, is one that is considered liberating by Dalits themselves. Thus, the blatant exclusion appears to be a tactic to dilute the movement against caste-based oppression prevalent in society.

In other words, the subject of the law (the individual) in a liberal society is viewed objectively, without any importance given to the individual’s context or history. The ignorance of the caste context in Kamble’s case is one such example. All the above observations point to the conclusion that the law has formally attempted to integrate marginal sections of the society, but, in reality, no such integration has occurred. The law still views the lower castes as the “other”, whom the law will more often subjugate, rather than liberate.

Kamble’s prior criminal record is testament to that. He has been booked under general laws with wide ambit, such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, and archaic, colonial laws such as the Dramatic Performances Act, 1876, demonstrating the State’s repeated effort to curtail freedom through any and all legal means. The trial depicted in the movie also reeks of ulterior motives on the part of the State. Rather than examining their own contribution in the death of Vasudev Pawar (no safety gear was provided, and the conditions in the gutter are so poor that he would have to be in an inebriated state to enter), they file a baseless, yet serious allegation of Abetment of suicide against Kamble.

The laws under which Kamble has been booked are perfect examples to explain how the hierarchy is maintained. When Kamble’s past run-ins with the law are brought up, the prosecution lawyer states that Kamble has been warned to not perform songs which are “seditious in nature and harmful to the general society”, given his violation of the Dramatic Performances Law; an archaic, colonial Act. Additionally, the Prosecutor claims that Kamble is a threat to “the sovereignty and integrity of India”, under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. The general wording of such laws lends itself to misuse by the State. The primary use is to curtail any disturbance of the class/ caste hierarchy. It is this aspect of the law that gives the State the power to repeatedly incarcerate Kamble.

The general, vague wording of the law serves another useful purpose for the State. It gives the impression of universal applicability; applicable even to those belonging to the upper echelons of class and caste, whilst also de-politicizing the caste struggle. The former gives legitimacy to the law and the latter stifles any collective uprising. This de-politicization may manifest itself in the form of charging the deviating offender with ordinary, ‘non-political’ crimes. Abetment of Suicide is a ‘non-political’ act, yet Kamble’s words which allegedly caused the suicide were purely political in nature.

Although a number of laws have been enacted to curb caste oppression and violence, the gap between the law and lower castes (access to justice, that is) is still appalling. In the caste stratification, the upper caste Brahmans constitute the powerful class exercising control over the law. In the film, it is the government that bends the law to suit its needs, oppressing the lower-caste and maintaining its dominance. It exposes the true intent of the State to ensure that the upper-caste members of the society remain in a position to influence law and law-making, while the lower caste struggle to find a place in this exclusionary narrative of the State.