In 1962, the United States of America had been calling itself a democracy for centuries. In the month of April the same year, two White police officers attacked unarmed Black Muslims after a Friday meeting of the Nation of Islam (NOI) and killed one of them while severely injuring seven.

Later on, in May, Malcolm X, a Black Muslim civil rights activist, an intellectual, and a prominent member of NOI at that time, while addressing an audience of Black people and the issue of police brutality said:

“We have to go to the root. We have to go to the cause…we are denied not only civil rights but also human rights…Stop sweet-talking him (white man). Tell him how you feel. Tell him how-what kind of hell you have been catching and let him know that if he is not ready to clean his house up..he shouldn’t have a house. It should catch on fire. And burn down.”

Two years later, in 1964, April 3, Malcolm X delivered what is known today as “Ballot or Bullet Speech” at Cory Methodist Church in Cleveland and asserted that:

“I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.”

The speech was delivered a month after he left the Nation of Islam (NOI) because of growing differences in his political philosophy and that of the group’s leader Elijah Muhammad and the rigidity of the group which was preventing the formation of a larger movement among the Black communities irrespective of their religion, and nationality.

Almost 58 years later, George Floyd, a 46 years old Black man was murdered by White policemen in the middle of a road, in front of his own people, in the country which still called itself a democracy. The Black Lives Matter movement that followed was not only against police brutality in an isolated case but against the system of police and the colonial legacy of racism globally. The murder and the subsequent labeling of the protests as “riots” by White media was yet another reminder that the ‘nightmare’ that Malcolm X had so clearly outlined, has continued for decades.

Malcolm X Before the World Got to Know About Him

Born in 1925, May 19, as Malcolm Little (later in his life, he would replace Little with X as an act of separating himself and his community from an identity that their white slavemasters gave them) to Louise and Earl Little in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm X came from a home that had immersed itself in the resistance movement for Black emancipation. Both his parents were Black activists and identified as Graveyites part of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. After losing his father to a supremacist murder and the subsequent institutionalization of his mother, Malcolm spent his years as a foster child before turning 15 and moving in with his half-sister in Boston.

At the age of 21, in 1946 he was sent to imprisonment in a burglary case. It was during his stay in jail which continued for 76 months that he developed a love for reading. Still, in jail, Malcolm was introduced to the Nation Of Islam (NOI) as a Black religious movement that believed and propagated Black self-reliance and greatness by his brother, Reginald, and in 1948 after writing to Elijah Muhammad, became a member of NOI.

Read More: Remembering Fred Hampton and the Power of Coalition

Malcolm X did not have to be taught about the perilous life realities of the Black community. His lived experiences during which he survived through poverty, violence, loss, racial discrimination, incarceration handed him enough understanding to look on the other side of the shallowness and hypocrisy inherited in the American dream. But familiarizing himself with the teachings of NOI gave Malcolm explanations and a language to talk about his position in a nation that was built to coddle white people, where the government “itself has proven that it is either unable or unwilling to protect” Black communities.

Journey with the Nation of Islam (NOI)

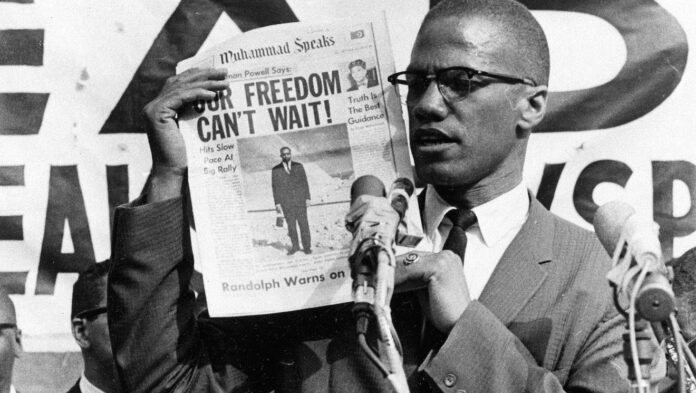

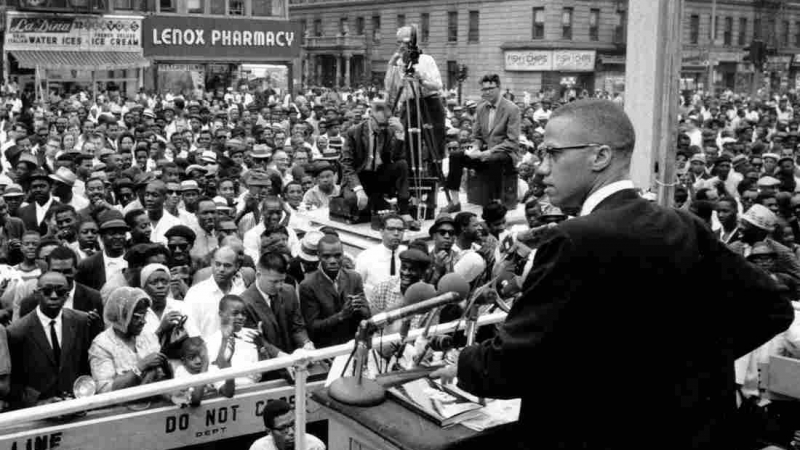

After his release on parole, he gained prominence in the organization as a Minister recruiting followers and conducting public meetings which were attended by huge crowds. His brilliant articulation of American racism, “there is no such thing as freedom for a black man in this country,” and straight questioning of the White population made him a known face in the media and a respected and beloved figure among the Black communities.

Image Source: Associated Press

When the NOI was being touted by the White supremacists as an organization that teaches hate, and Black Muslims were being projected as a separate group from the larger Black community, Malcolm X went on record to talk about questions of dignity, love, and concern for the Black communities that guided NOI’s argument of self-defense.

“Everybody would like to reach his objectives peacefully. But I’m also a realist. The only people in this country who are asked to be nonviolent are black people” he said meaning that it was the violence perpetrated by the Whites on Black communities that needed to be questioned— a nuance that still eludes those who occupy positions of power.

Moving Beyond the Political Passivity of NOI

Malcolm was not at peace with the political passivity of NOI and was often questioned by the group for being politically vocal in public. Even though he started identifying himself as a Muslim since the time he joined NOI, it was after his pilgrimage to Mecca and the subsequent conversion to Sunni Islam that got him a new name— el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, that as he himself said, his understanding of Islam deepened.

In a letter from Mecca he wrote, “all I have seen and experienced on this pilgrimage has forced me to “re-arrange” much of thoughts pattern and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions. This “adjustment to reality” wasn’t too difficult for me to undergo, because, despite my firm conviction in whatever I believe, I have always tried to keep an open mind.”

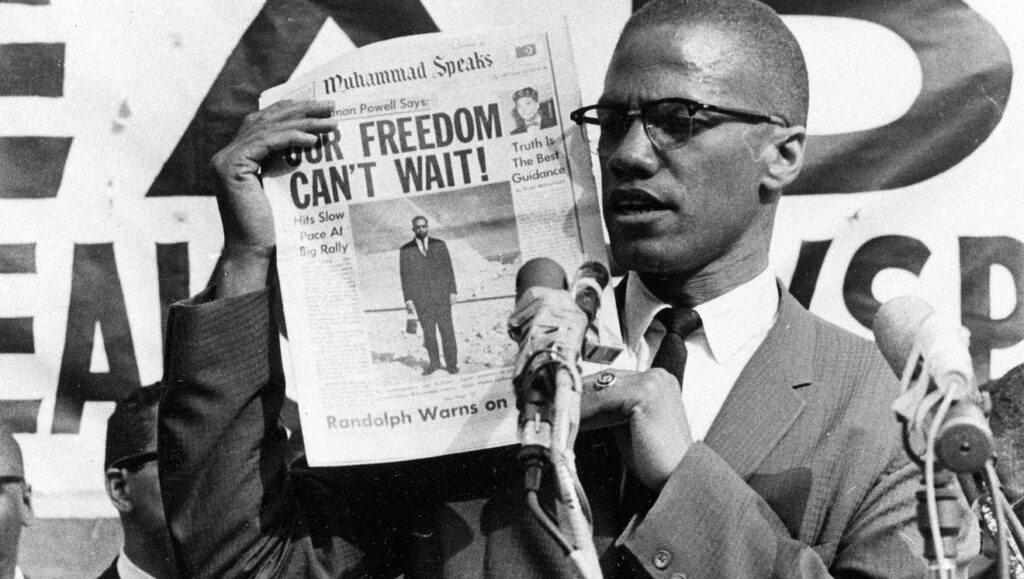

Image Source: Associated Press

Malcolm X grew out of dogma that existed in NOI. In 1964, he founded Muslim Mosque Inc (MMI), a group that engaged in Islamic teachings and issues of racism. On his return from Hajj, he formally separated from the NOI in 1964. That year in his life was filled with intense travel, speeches, national and international recognition, heavy surveillance by the government, and also strings of death threats and symbolic attacks on him by NOI.

As an intellectual and an activist he wasn’t afraid to self introspect and grow as he learned more about people and philosophies. He did not see this process as a sign of weakness of thought that very commonly forces public figures to stick to the dogma but as an essential part of understanding the society so as to work for its transformation.

Malcolm X’s Emphasis on Forging Solidarities for a Revolution

Malcolm’s philosophy which puts emphasis on the essentiality of building movements with oppressed Black people without religion being its focal point and at the same time continuous assertion of his Muslim identity challenges the Islamophobia that the non-Muslim white states have purposefully propagated especially after 9/11 in states in the name of ‘terrorism’.

He pushed for a politics which would engage in reclaiming Black dignity, culture, language, its defiance, and its history and demand aggressively for structural changes, unlike the conventional Black civil rights movement which at that time focused primarily on racial integration. He furthered his analysis of racism to include the political economy of racial discrimination and the growing imperialist tendencies at that time and called for the transnational mobilization of black people with their internal differences with a shared history of slavery and colonial violence. Following this line, in June 1964 he founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), a pan-Africanist organization. It was during one of his addresses to OAAU in Harlem that he was assassinated on February 21, 1965, in a hall filled with more than 400 people.

Malcolm X scared the white supremacists as much as he scared the liberals as well as groups like NOI because of his success in making the Black people realize that they have the power to fight back when they join hands instead of fighting as separate factions. He was not just popularly followed by Black people but was and continues to be deeply loved by them. It was during his funeral that actor, writer, and activist Ossie Davis famously mourned, “our shining black prince … who didn’t hesitate to die because he loved us so.” He further added, “if you knew him you would know why we must honor him.… And, in honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves.”

We live in a world where the value of human life in itself has been lost to capitalist profits while the world continues to struggle against patriarchy, casteism, racism, islamophobia, xenophobia amongst other things. The contemporary relevance of Malcolm X’s political thoughts and actions lies in their embeddedness in radical love, radical anger, and radical justice that cuts across socially constructed differences to forge solidarities that recognize revolution and not mere integration as a solution.